Why is count++ not thread safe

/ 6 min read

Table of Contents

Incrementing a number

Let’s say that you have a variable called count and you want to increment it. It’s simple, we just do count++ (at least in c/c++), but lets say I want to increment the count variable faster, again, the solution is simple, we add more threads. First, lets add to the count variable using just one thread:

#include <iostream>using namespace std;

int count = 0;

void increment() { for (int i = 0; i < 100000; i++) count++;}

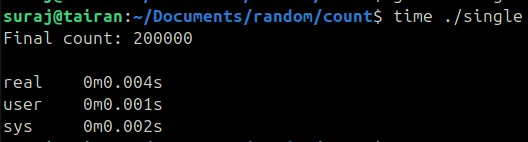

int main() { increment(); increment(); cout << "Final count: " << count << endl;}And we get the output as

We can see that it has taken 4 milliseconds to execute this program, now to make it faster, we can add extra threads to increment the count variable, lets see how it can be done

We can see that it has taken 4 milliseconds to execute this program, now to make it faster, we can add extra threads to increment the count variable, lets see how it can be done

#include <iostream>#include <thread>using namespace std;

int count = 0;

void increment() { for (int i = 0; i < 100000; i++) count++;}

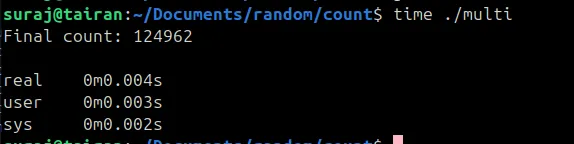

int main() { thread t1(increment), t2(increment); t1.join(); t2.join(); cout << "Final count: " << count << endl;}When we compile and run it, we get the following output

WHOA! What happened there?? The output is wrong, lets try again a few more times

WHOA! What happened there?? The output is wrong, lets try again a few more times

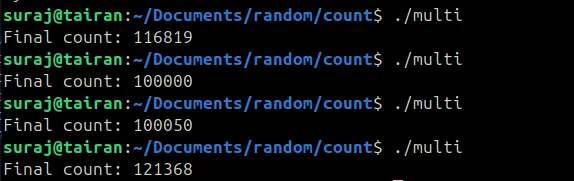

HUH, the output is not just wrong, it’s different everytime. But, computers aren’t supposed to make mistakes right?

HUH, the output is not just wrong, it’s different everytime. But, computers aren’t supposed to make mistakes right?

To understand what’s happening we need to dig deeper.

Race Conditions

To understand what happened above, we need to first break down two key ideas:

- Addition is not just one operation

- Operating systems can preempt threads at any time.

Addition is not one operation?

At first glance, it might look like addition is supposed to be only one step , but that’s not actually the case. When we want to add two numbers together, the computer actually does 3 operations

- Read - load the value from memory into a CPU register.

- Modify - perform the addition in the register.

- Write - store the result back into memory.

So even though we write count++, under the hood it’s really a read–modify–write sequence. Keep that in mind, because it’s about to bite us.

Preemption

Modern operating systems use preemption to give every thread a fair share of the CPU. Preemption means the OS scheduler can pause a running thread at almost any instruction, save its state, and let another thread run. This is what makes multitasking possible: while one thread is waiting on I/O, another can keep the CPU busy.

Preemption is a vast topic that dives into scheduling algorithms, context switching, interrupts, and priority levels. That’s a whole universe of its own, but for now, all you need to know is: because threads can be paused at any point, even “tiny” instructions like ++ can interleave in unexpected ways.

Putting it all together

Now let’s see how these two pieces collide. Suppose we have two threads, T1 and T2, both trying to increment the same variable x. We’d expect x to end up as 2. But here’s one possible sequence of events:

| Step | T1 | T2 | x |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Read x=0 | 0 | |

| 2 | tmp=x+1 | 0 | |

| 3 | Read x=0 | 0 | |

| 4 | tmp=x+1 | 0 | |

| 5 | Write 1 | 1 | |

| 6 | Write 1 | 1 |

Here’s what went down: T1 loaded x and calculated tmp=1, but before it could write it back, it got preempted. T2 then ran, loaded the old value of x (still 0), added 1, and wrote 1 back. Later, when T1 resumed, it stored its stale result of 1, overwriting T2’s update. Both threads “incremented” but the final result is 1 instead of 2.

In another run, things might look like this:

| Step | T1 | T2 | x |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Read x=0 | 0 | |

| 2 | tmp=x+1 | 0 | |

| 3 | Write 1 | 1 | |

| 4 | Read x=1 | 1 | |

| 5 | tmp=x+1 | 1 | |

| 6 | Write 2 | 2 |

This time, the final result was correct, but only by chance. The OS happened to schedule the threads in an order that avoided the conflict.

And that’s the key point: the output isn’t predictable. Depending on timing and scheduling, you might get the right result, the wrong result, or something else entirely.

This unpredictable behavior, where multiple threads access and modify the same shared variable without proper synchronization, is what we call a race condition.

Mutexes: The First Fix

So how do we stop two threads from trampling over the same variable? The idea is simple: only let one thread at a time enter the section of code that touches count. This is where a mutex (short for mutual exclusion lock) comes in.

Think of a mutex like a key to a room. If Thread 1 grabs the key and goes inside to update count, Thread 2 has to wait outside until the key is free. That way, there’s no way they can scribble over each other’s work.

Here’s the same program, now with a mutex added:

#include <iostream>#include <thread>#include <mutex>using namespace std;

int count = 0;mutex m;

void increment() { for (int i = 0; i < 100000; i++) { m.lock(); // grab the lock count++; // critical section m.unlock(); // release the lock }}

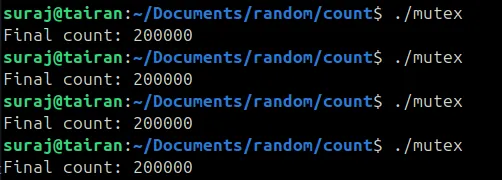

int main() { thread t1(increment), t2(increment); t1.join(); t2.join(); cout << "Final count: " << count << endl;}After we compiling and running it, we get the following output

Now no matter how many times you run this, you’ll always see the correct output: 200000. The mutex guarantees that only one thread touches count at a time.

Of course, this comes at a cost. If you imagine 100 threads all trying to increment the same variable, 99 of them are basically just standing in line, waiting their turn. Under the hood, a mutex might even involve system calls (like futexes on Linux) to put threads to sleep and wake them up again, and that adds overhead.

But still, mutexes are the simplest way to fix race conditions, and they’re battle-tested. For now, it’s enough to know: mutexes trade speed for safety.

Wrapping up

So what started out as an innocent count++ turned into a full-blown mystery:

-

We saw how something that looks like a single step is actually a three-part read–modify–write process.

-

We saw how the OS can barge in with preemption and shuffle threads around mid-instruction.

-

And we fixed it the classic way, by putting a mutex around the critical section.

But mutexes aren’t the end of the story. They’re safe, but they’re also heavy, like using a traffic cop to manage two kids sharing a toy. Surely there’s a faster way, one that lets threads cooperate without constantly waiting their turn?

That’s where atomics and lock-free programming come in. In the next post, we’ll peek under the hood of hardware instructions designed to do exactly what we need: fast, thread-safe updates without the baggage of locks.

So stay tuned, we’ve only scratched the surface of concurrency. The wild stuff is just getting started.